In April 2005, I embarked upon a sci-fi/fantasy reading and writing extravaganza. After years of armchair rivalry with novelists - I hadn't even written a book yet, let alone had one published - I finally put my boasts of "I could write that!" to the test.

My weapons were the masters of the genre - Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs. I delighted in Verne's Mysterious Island, devoured Burroughs' John Carter of Mars series and was frankly awed by a '2 in 1' edition of Wells' The Time Machine and War of the Worlds. Over the next six months, I also managed to squeeze in 2o,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Island of Dr. Moreau, The Land That Time Forgot, Burroughs' Pellucidar cycle and two novels by H. Rider Haggard, King Solomon's Mines and She.

"Tally-ho!" How could I write any other way? The eloquent (often wordy) prose of those fine authors cast such a spell over my first attempt at a novel that when I later came to re-read what I had done, I couldn't believe how Victorian my sentence structure, vernacular and verbal formality had become. Words like "ingress", "precipitous" and "whither" peppered my prose. Of course, my novel was a time travel adventure and did have an upper crust Englishman in the title role, but the totality of this classical influence took me aback. In short, I knew it could never be published in the twenty-first century.

"Rotten luck, old chap."

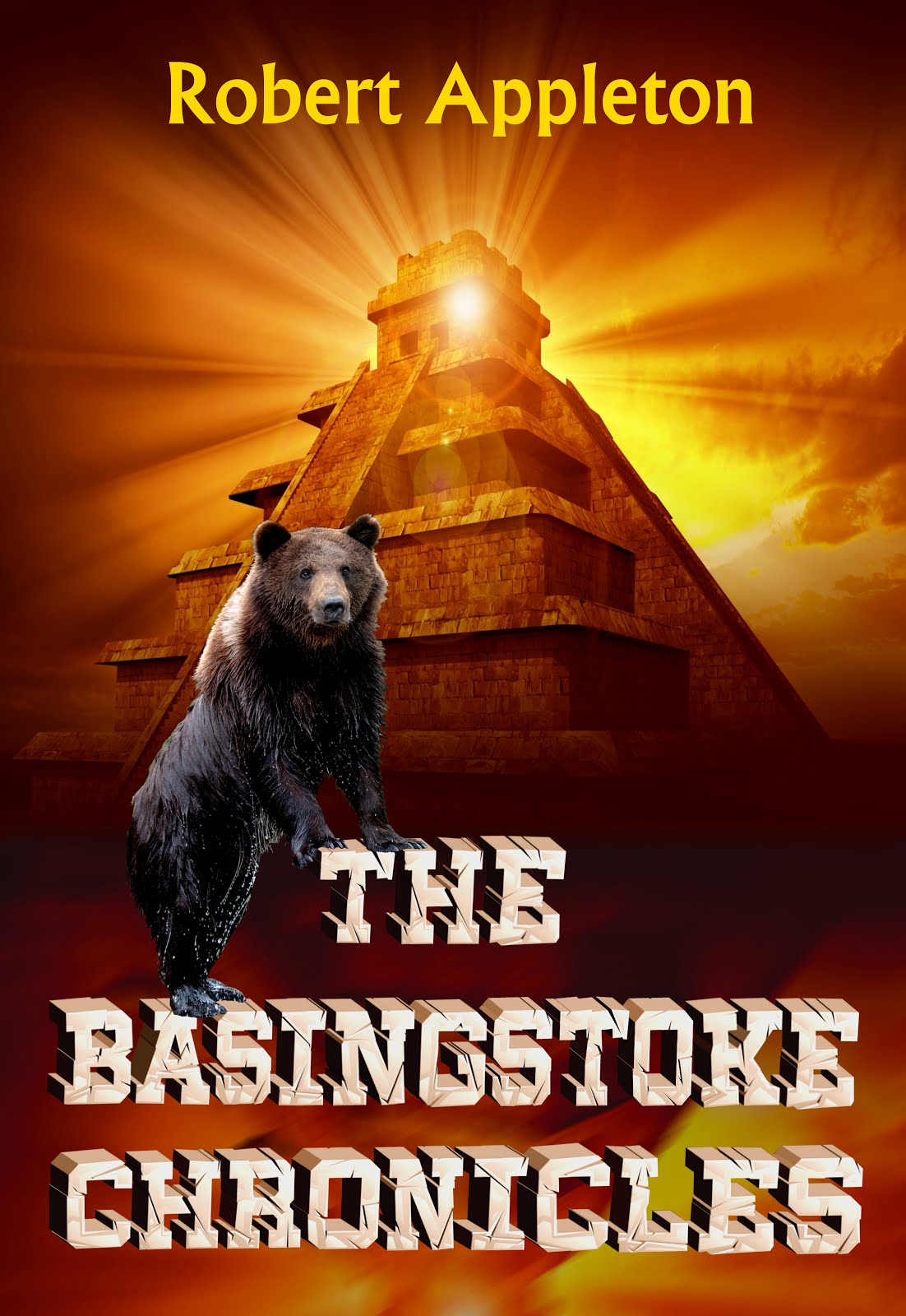

It was a bittersweet achievement. Six months' work had resulted in a pretty good, epic adventure with no hope of publication. The Basingstoke Chronicles, as it later became, was a victim of too much research - and not enough. I had exhausted the classical greats yet failed to ground the work with a modern sensibility. The story was circuitous, like many of Burroughs' - a tale within a tale, which the hero recounts to his friend on a deserted cove in Devonshire, Southern England. And the time travel aspect was integral, not merely a gimmick to reach another world. The spirit of the book was more speculative than postmodern, naive as opposed to ironic, an intrepid excursion into the unknown, a la Haggard.

In the meantime, I went off to write other things, including romantic sci-fi survival series The Eleven-Hour Fall and WW2 action horror Sunset on Ramree, but I never attempted another full-length novel. The sheer time and effort I'd spent on what had ultimately become a folly, left me reticent.

I'm now a published author of four e-books. The "modern" writing style flows easily (and more simply) and I'm about to embark on a part-time writing career. So the other day I thought it amusing to look back over Basingstoke and see what had gone so awry. To my genuine surprise, I ended up loving what I'd written!

The story remains intriguing, the mystery is a good one and the characters are clearly defined and fun. Yes, it reeks of Burroughs, Verne and Wells - in an amateur sense - but I realized that I'd in fact achieved everything I'd set out to. A classical-styled time travel adventure.

I've re-written it for pacing, passive voice, wordiness and repetition. I've tightened scenes and clarified the sci-fi exposition. It's now 10,000 words shorter. But, by and large, it's The Basingstoke Chronicles I dismissed so completely three years ago.

Will it ever get published? Who knows? Maybe I really would have to stumble upon a time machine. I suspect Victorian presses would gladly offer it as a twopenny serial. A few shelves below The Land That Time Forgot. No one would be happier than I, of 2008.

And you know what? It inspired me to write the prologue for a new sci-fi novel - my best piece of writing yet. And who was the first name off the bookshelf this time? Carl Sagan. Hey, it's not like I'm ambitious or anything...

Why Movies Don’t Matter Anymore

-

Jerry Seinfeld was interviewed for GQ, and he dropped this truth bomb:

“Film doesn’t occupy the pinnacle in the social, cultural hierarchy that it

did for ...

3 hours ago